The ten months before the onset of Covid lockdowns in Western Europe saw an unprecedented number of general elections. But since the pandemic began there has been a glut of electoral contests. How do the main party families square up ahead of the resumption of electoral hostilities in 2021?

Between April 2019 and February 2020 more than 117 million voters participated in 11 general elections across Western Europe. Only six of these elections were scheduled to take place in this period. A combination of cabinet and constitutional crises accounted for the others. The next scheduled election on the continent is not until March next year – an unprecedented hiatus in electoral competition that has coincided with the Coronavirus pandemic and the massive disruption to social and economic life in brought in its wake. What does the most recent round of elections tell us about the balance of political forces across Western Europe? And how might the main party families position themselves in the emerging new normal?

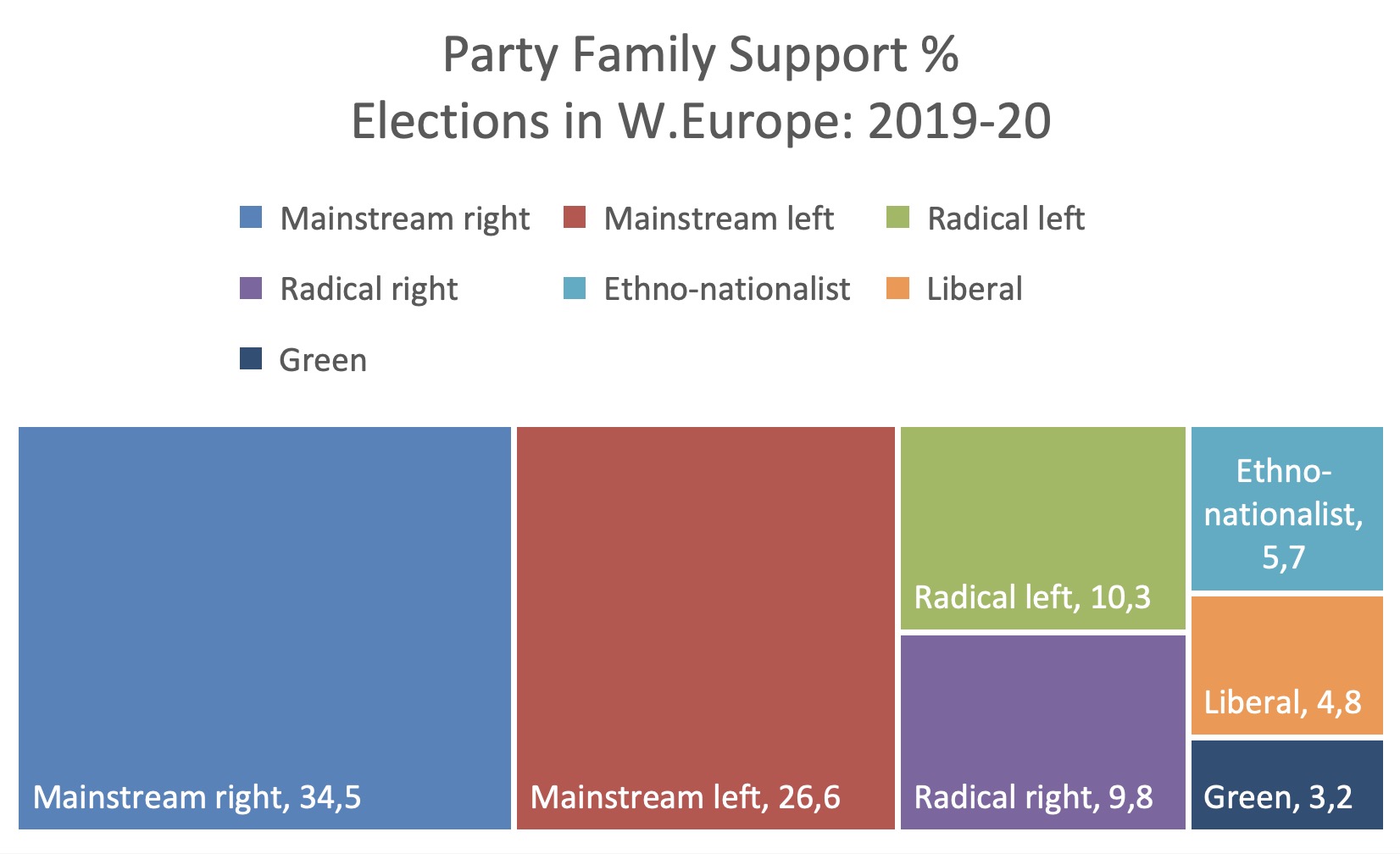

The performance of Western Europe’s seven main party families in the 11 elections of 2019-20 is illustrated below. Mainstream parties of the right and left dominated, buoyed by strong victories for the right in Austria, Greece, and the UK, and for the left in Portugal and Spain. However, radical competitors to mainstream parties from the left and right attracted a fifth of all voters – a total of 23.6 million – while parties seeking to break-up their respective nation states drew in another 6.7 million voters. The West European party landscape is clearly highly fragmented with well-backed challengers to the party and state systems of the continent.

All of these elections predated the dramatic falls in GDP caused by the lockdown, and took place in a year (2019) of economic growth for all the countries involved. A long and uncertain winter lies between now and the coming elections but we can identify some key questions for the main party families who will contest them. Can the mainstream right combine the projection of competence during a crisis with a nod to the populist appeal of the radical right. Can the mainstream left convince weary electorates of the benefit of state led solutions to climate and economic crises? Will radical parties of the left and right be able to convince with stories of system failure? And can the Greens capitalize on the growing awareness and sense of urgency of the need for climate action? The voters of Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands and Norway hold the answers to these questions and psephologists starved of new electoral data await their response with bated breath!