The 2010’s were declared the most electorally turbulent decade in the history of Western Europe.[1] The Dutch electorate have contributed much to this turbulence. Average electoral volatility in the Netherlands in the 2010’s measured 21, compared to 17 in Western Europe as a whole. However at yesterday’s General Election the Dutch signaled a return to more stable times, displaying the lowest level of electoral volatility since 1989. Is the Dutch case part of a wider return of Europeans to more stable patterns of party attachment?

Electoral volatility is a concept that captures the stability of voter choice at the system level. It is measured by adding the sum of the vote change of all parties at an election and dividing that sum by two. Following a period of heightened instability in the inter-war period, voters were understood to be increasingly bonded to parties by social and cultural ties. This translated to greater party loyalty in the period 1945-1985 (see Bartolini and Mair, 1990). Since the mid-1980’s however these trends reversed with nearly all Western European countries experiencing rising and record levels of electoral volatility.

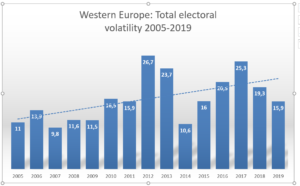

The following chart shows average electoral volatility at elections in Western Europe between 2005 and 2019. The upward trend is clear with peaks in 2006, 2012, and 2017. Since 2017 however there have been signs of a reversal of this trend, with volatility in 2019 no higher than 8 years earlier.[2]

Source: the author

Yesterday’s Dutch election is one of four scheduled for 2021 in Western Europe. If we take the current state of the opinion polls in the other three countries[3] – Germany, Iceland, and Norway – we get an early, if imperfect sense, of what 2021 holds in store. All four countries last held general elections in 2017 so there are two main ways to draw comparisons.

The first is to compare an estimate for volatility in each country in 2021 with actual volatility in 2017. Only in Norway where volatility was 9.1 in 2017, do current opinion polls predict an increase in volatility. In Germany and Iceland falls of respectively 5.4 and 7.8 in total volatility are predicted by the polls while in the Netherlands actual volatility fell by 9.8 points.

The second is take an average value for volatility at the four elections due this year and compare them with both the annual Europe-wide average for previous years and the average for the four countries when they last went to the polls. On the basis of one actual result and three sets of opinion polls the average electoral volatility in Western Europe in 2021 may be estimated at 13.4. This represents a further annual fall and a near halving of volatility compared to 2017 overall. And compared to the actual average volatility for the four countries in 2017, our 2021 estimate represents a fall in total volatility of some 4.8 points. The evidence for a continuing downward trend in total electoral volatility seems compelling.

There are two reasons to be cautious about this speculation. First, a lot can happen between now and the next round of General Elections and leaving plenty of room for voters to shift back to greater volatility. Second, electoral volatility in Western Europe has exhibited downward patterns before only to surge again to new highs. In the medium-term volatility may bounce up again if the Governments of Western Europe return to austerity to manage the budget costs of the Coronorvirus pandemic, shifting those costs onto taxpayers and workers in the public sector. Political scientists though will be scrutinizing these trends for signs of the return of the long-lost attached voter.

[1] See https://twitter.com/Vinceman86/status/1206538494497214464

[2] There was just one General Election in Western Europe in 2020. The Irish election in February that year had total volatility of 17.2, down 7.6 points compared to the previous election in 2016.

[3] The most recent opinion poll in Germany, Iceland and Norway as of 18th March.